widescreenmuseum.com

The next big thing in cultural preservation: indie and art-house cinemas, and their need to buy (and maintain) costly new digital projectors.

As with many adapt-or-die technology transitions, it’s partly propelled by money. In this case, it’s the money of the big Hollywood studios.

They now spend more than a billion dollars each year making and shipping film prints. They’d rather spend that on supporting artistically ambitious but less commercial filmmakers cocaine and whores.

The studios want all theaters to convert to digital, as quickly as possible. They’re offering financial incentives to theaters who accept movies on hard drives instead of 35mm reels.

(As I briefly explained a few years back, the digital formats for theaters are called “2K” and “4K.” The latter offers about four times as many pixels as Blu-ray discs, or about 10 times the detail of DVDs. Theaters receive “digital prints” on hard drives, inserted into specially made projectors. The exhibition side of digital cinema is called “DCP” (for “Digital Cinema Package”.))

Already, the studios are refusing to rent out 35mm prints of many classics. Within three years, they might not send out any films on, you know, film.

Even with the studio incentives (which come with significant restrictions and which smaller distributors can have trouble matching), the transition’s tough enough for the big chain cinemas (where attendance is the lowest it’s been since the mid 1990s).

For the smaller operators and the nonprofit exhibitors, the cost could be fatal. But if they stick with only analog equipment, they might have nothing available to show on it.

•

And if film factories and labs lose the business of theatrical prints, it might not be financially feasible to make and process 35mm film for movie cameras.

Which brings us to the other end of the process.

Many directors (not just the George Lucases and James Camerons) now prefer to shoot their movies digitally.

It’s more versatile than film. It reduces the time needed to set up a shot. It makes 3D and other special effects a lot easier. It allows more and longer shots (including the single continuous take that is Russian Ark). The equipment’s smaller, less delicate, and easier to learn. Outtakes don’t waste costly film. Directors can shoot more “alternate takes,” then decide during editing which ones best fit a film’s overall pacing.

Digital shooting has also been a godsend for documentaries and indies. The whole Seattle independent filmmaking scene of the past decade has relied almost entirely on digital shooting.

•

But the technology that’s a boon to people who make indie movies is a burden to people who show them.

Nationally, about two thirds of all theaters have DCP gear. The two SIFF Cinemas are already digitally equipped, as are the chain-owned theaters SIFF uses during the festival. (Though the process has had its hiccups.)

As for the rest, they could settle for showing digital movies (from non-major distributors) on lower-res Blu-ray or even-lower-res DVD discs. (This is what the Northwest Film Forum’s apparently doing, at least for now.) For smaller rooms with smaller screens, Blu-ray output might be good enough. It displays almost as many pixels as the 2K digital-cinema standard (but doesn’t have the extra-tuff copy protection and other Big Brother features the big studios demand). And because Blu-ray uses mass-market gear, it’s a lot cheaper for both exhibitors and distributors.

Or they could combine hi-res projectors with hi-bandwidth Internet connections or satellite dishes, to get programming direct from the distributor. (That’s what those cinema airings of live Metropolitan Opera shows use.)

Or they could spring for DCP, even with its cost and its studio-decreed operational restrictions. Some nonprofit art houses might need special fund drives for the gear, which starts at around $60,000 without 3D capability.

Or they could just close up shop.

One industry analyst guesses maybe 5 percent of the country’s current 5,700 cinemas could close due to the digital transition. Many of those could be small-town theaters and drive-ins, whose big-studio fare will become available only via DCP.

•

Then there’s the little matter of storage and presentation.

Digital editing and retouching have done wonders for film restoration.

But nobody knows yet how long the physical media on which the digits are stored will last.

Or whether the machines to play them will still exist in future centuries.

For foolproof long-term keeping of movies, there’s still nothing like real film.

•

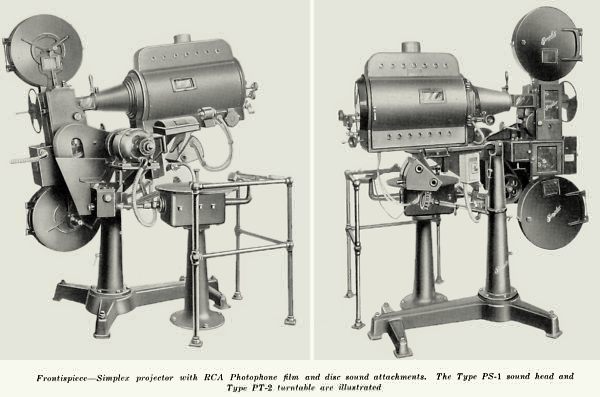

P.S.: I’ve linked to this before, but this post is the perfect excuse to re-link to it. It’s my favorite work of “technical writing,” a pinnacle of depth and clarity. It’s a 1930 RCA instruction manual for movie theater operators, teaching them how to properly present those newfangled talking pictures.

P.P.S.: Even with digital’s cost advantage, many filmmakers defiantly still film and edit on actual film. And now, for the first time in 50 years, a film is being made in original three-strip Cinerama!